LISTEN TO THIS ARTICLE

Introduction

Discussing the analysis of confiscatory taxation in modern times involves addressing situations where taxes significantly erode economic capacity, posing limits to collection goals and tax progressivity, highlighting the extraordinary nature of such scenarios.Excessive taxation, which absorbs a substantial part of a person’s income and wealth, has been questioned both from a legal and economic point of view.

Tax confiscation is a very controversial matter that shows that talking about taxes is talking about politics. Let's put forward some extreme positions.

Margaret Thatcher said “If envy prompts policies of confiscatory taxation against the successful, everyone loses. Talent flees the country. Wealth generation slows” (1991).

At the opposite extreme we find positions such as those of Oxfam and ActionAid, which proposed a 50%-90% tax on these extraordinary profits of large corporations. This could then be used to “help people struggling with hunger, rising energy bills and poverty in rich countries, and to provide hundreds of billions of dollars to support countries in the Global South.” .

We will leave aside these questions of political ideology and next address some economic and legal aspects involved in this controversial matter.

Property and taxes

The right to property is not an absolute right, but, like all rights, it is limited. Here, we can mention the expropriation -with compensation – for purposes of public utility, the confiscation [2] – without compensation – and also the contributions and taxes that the States may establish on the wealth.

Property and taxes need each other, since without property there is no economic source to pay taxes, and without taxes there is no state to protect the property. The challenge is to find a sustainable middle ground.

Confiscatory taxation

Talking about the confiscatory aspect of a tax is not entirely correct since it refers to a repressive and restrictive measure of property.

The Supreme Court of Justice of Argentina understood this at first, when it rejected the possibility that a tax could be branded unconstitutional by its confiscatory aspect, since it is a lawful act of the State that could not be confused with the sanction provided for and prohibited in the constitution. Subsequently, the court admitted that a tax, validly imposed by Parliament, could, in certain exceptional cases, absorb a substantial portion of the capital or income achieved and consequently lose – and in that proportion – its constitutional validity.

Some legal aspects of confiscatory taxation

There are certain fundamental principles that limit the tax power of the State, among others: the principle of legality, the contributory capacity, proportionality, private property, free exercise of an activity, freedom and private initiative, among others.

Not all countries expressly contemplate the prohibition of confiscatory taxation, although such protection arises from considering other principles related to the right of property, freedom, contributory capacity, etc.

For example, in Spain, according to the Constitution, a tax is “legitimate” if, “according to the law” (art. 31.3) it taxes the “economic capacity” and it does not have a “confiscatory scope” (art. 31.1). The economic capacity constitutes not only the justification of the duty to contribute, but also the determining element of the amount in which to contribute. When the “confiscatory scope” is prohibited, an attempt is made to guarantee respect for other constitutional values and rights such as the right to private property (art. 33).

Juan Ignacio Moreno Fernández [3], in allusion to the role of justice in this issue, recalls that in Germany, a tax was labeled as confiscatory when it imposed an “exaggerated burden” (from 50%[4]). In France, itis when it generates an “excessive burden” (from 50%), in Argentina when it absorbs a “substantial part” of the property or income (although at some point he understood that it occurs when an inheritance tax approaches 33%) and in Spain, when it taxes fictitious manifestations of economic capacity or when it exhausts the taxable wealth.

Some economic aspects of confiscatory taxation

Taxes produce effects beyond those merely collected, and depending on the type and purpose, there are certain considerations regarding their economic and social implications.

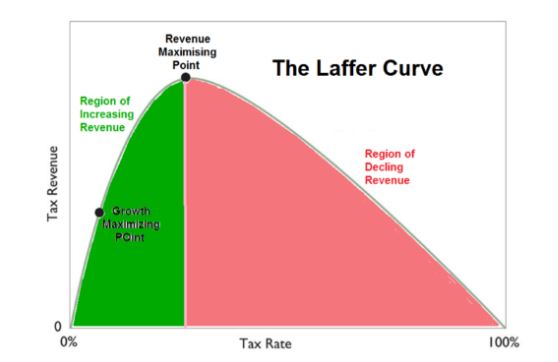

The Laffer curve highlights the effects of disproportionate taxation. Graphically the collection, depending on the rate, will first increase, and then decrease [5]. Every rate increase does not necessarily produce an increase in revenue and at some point, it even begins to decrease. At that point difficult to determine – the incentives to avoid paying (evasion, informality, etc.) begin to produce effects, therefore the taxation becomes excessive.

Confiscatory taxation according to the tax rates

The tax that affect non-existent or fictitious manifestations of economic capacity may be questioned as unconstitutional if confiscatory, as well as when taxing real or potential manifestations of economic capacity, it exhausts the taxable wealth or a substantial part of it, by demanding a disproportionate sacrifice.

A confiscatory tax analysis should consider that taxes are not all the same. Specifically, regarding the possibility of transferring or not a tax, which at some point was used to differentiate indirect taxes (VAT) and direct taxes respectively, it has been shown that even the latter could be transferred to customers or suppliers, as the respective price elasticities allow.

There are currently no doubts about the justifications for taxing the wealth or the property, as well as consumption and income, as manifestations of contributory capacity, but also as a consideration for the property protection service provided by the State.

According to Juan Carlos Benítez and Fernando Velayos [6]when a “stock” type asset is taxed, the legislator is presuming that this wealth generates returns with which the tax can be paid. That is, a rate of 2% is implying that the equity generates more than a 2% return.

These authors mention two options to remove the risk of confiscation in a wealth tax (i) establish an extremely low rate, the level of which ensures that the average return on equity will be higher than the levy and (ii) provide a limit to the taxation of wealth, as France did, [7] or Spain [8].

The above also highlights the debate on whether a confiscatory analysis could consider the effect of a tax, or the concurrence of several taxes on the same subject or taxpayer, including the existence of subnational states with applicable taxing power.

Another issue that could enter the debate is whether accessories, such as late payment interest and applied penalties, should be part of this analysis.

Finally, it is worth asking whether the tax rate is the relevant element to be considered or whether other elements should be considered, as well as the national – and international- context, and the taxpayer’s situation. Certainly, a rate in itself does not say much, but certain elements that influence the determination can have the effect of the tax becoming confiscatory, for example, in the income tax, not to admit the monetary correction due to price increases.

The doctrine has also said that the limit of the confiscatory taxation derives not only from the tax paid, but also from considering the level and quality of the public services provided by the State and, why not, from considering an exceptional context that demands urgent and emergency public resources, such as a war or a global pandemic. As you can see, the debate has several sides.

Double taxation and confiscation

Two States can concur with their powers of taxation and generate double or multiple taxation effects.

Although a taxpayer could claim that this concurrent taxation absorbs a substantial part of their income or wealth, there is no doubt that there are mechanisms to solve or at least mitigate it, which should act to solve this issue. Unless there is a supranational legal framework that is violated, there is no possibility of confiscation claims before one of the States.

Final words that do not close the debate

Finally, we can conclude that excessive taxation could generate harmful economic effects and affect the fundamental rights of individuals. The great challenge is to delimit, in the specific case, those assumptions that evidence a confiscatory situation. Undoubtedly, it is up to the taxpayer to prove it, showing that a tax absorbs a substantial part of his income and assets.

However, at the other extreme, some voices at this inaugural IFA (2023) round table warned that the estimated evasion in Latin American countries exceeds 6% of GDP -plus informality-, representing subjects with untaxed -or insufficiently included- income and wealth, Therefore, and in order to cover the need for public resources that the countries of the region particularly have and to safeguard the principle of equality and equity, it is a priority that the Tax Administrations dedicate efforts to those issues and use the powerful techniques and technologies available (AI, data mining, blockchain , as well as the exchange of tax information between the States.

[2] “To confiscate” comes from the Latin “confiscare”: to incorporate into the wealth of the state. Confiscation and forfeiture depriving the patrimonial effects of a crime are related.

[3] “La prohibición de confiscatoriedad como límite al tributo” in Revista Técnica Tributaria // issue 124 January – March / 2019.

[4]The most famous case law comes from the German Constitutional Court (June 22, 1995), which declared unconstitutional any tax or combination of them, exceeding 50% of the income obtained by the taxpayer in the financial year.

[5] The mathematical foundation is Rolle’s theorem, according to which, if tax revenue is a continuous function of the tax rate, then it has (at least) a maximum (since it is an always positive function) at an intermediate point of the interval, but not necessarily at the center.

[6] Taxes on the Wealth or Assets of Individuals with special mention to Latin America and the Caribbean © 2017 Inter-American Center of Tax Administrations (CIAT).

[7] The so-called tax shield of residents in France was set at 75% of their total net income in 2016 (including some tax-exempt).

[8] The sum of the income tax plus the Wealth Tax was set at 60% of the net income, but with a reduction of the latter up to 80%.

Disclaimer: Content posted is for informational and knowledge sharing purposes only, and is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice related to tax, finance or accounting. The view/interpretation of the publisher is based on the available Law, guidelines and information. Each reader should take due professional care before you act after reading the contents of that article/post. No warranty whatsoever is made that any of the articles are accurate and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for tax or accounting advice.

Contributor

Related Posts

The UAE has introduced a new top-up tax regime as part of its commitment to global tax reforms und...

Read More

Anti Money Laundering is often viewed as a complex regulatory requirement. In reality it plays a sim...

Read More

Trade and commercial activity form the backbone of regional economic growth. Large volumes of goods ...

Read More